>>Translation by Jędrzej Majer<<

When I decided to write this article I asked myself: what do I know about that country? It became very apparent very quickly that the answer is: “not much”. I have some foggy memories about feelings of solidarity in times of the Soviet Union, as well as anti-Soviet jokes about dishonest public media, revolving around the mythical Radio Yerevan. Maybe you can remember them too. You also remember the Armenian Genocide, which is a well recorded one, contrary to what Hitler believed when he ordered the attack on Poland in 1939 (“[…] send to death mercilessly and without compassion, men, women, and children of Polish derivation and language. Only thus shall we gain the living space, […] which we need. Who, after all, speaks to-day of the annihilation of the Armenians?”).

When I decided to write this article I asked myself: what do I know about that country? It became very apparent very quickly that the answer is: “not much”. I have some foggy memories about feelings of solidarity in times of the Soviet Union, as well as anti-Soviet jokes about dishonest public media, revolving around the mythical Radio Yerevan. Maybe you can remember them too. You also remember the Armenian Genocide, which is a well recorded one, contrary to what Hitler believed when he ordered the attack on Poland in 1939 (“[…] send to death mercilessly and without compassion, men, women, and children of Polish derivation and language. Only thus shall we gain the living space, […] which we need. Who, after all, speaks to-day of the annihilation of the Armenians?”).

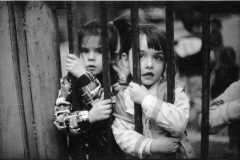

Bearing all this in mind I wanted to break off with clichés we have stored in our shared memory and find out what Armenia looks like today. Find out about its people and its life. A chance encounter made it possible through photography of Norayr Chilingarian. His works are focused on recording a sham lack of beauty and perfectionism, as well as coarseness that seem to be a characteristic trait of the city he lives in – Yerevan.

Are you a Yerevanian? Please tell us how your adventure with that city began and what made you start taking pictures of it.

I am not sure I can call myself a Yerevanian. I do not have a strong confidence that I actually grew up in Yerevan. I probably grew up in my room, reading science fiction.

However, I was always interested in the city. I explored it, I wanted to know every path, narrow staircase or shortcut through a residential area. Should anyone chase me, I knew a gate I can slip through, which looked just like a regular private house door, but it was not, and it led to an area with multiple exits. I also liked roofs. Unfortunately, most of them are locked nowadays.

Maybe it is because I am a control freak and I would like to know every nook and cranny of the city I live in. Similar to how I want to know everything about an operating system I use.

You seem to choose less popular shots; apartment blocks, slums, faces of people in a hurry and a variety of dogs. A Polish poet once said: “I prefer ugliness, it’s closer to the bloodstream.” Do you feel the same way? Do patchy and unfeigned surfaces strike you as more related to real life?

I do not think in terms of popular or unpopular.

I like life and I like sincerity. I tend to go where I can find traces of life, a good example is backyards. There, a kid wrote his name or a dirty word on a wall. This is a trace left by life. I also like taking photos of poor houses, maybe because I believe they are well-designed and beautiful. An explanation to this phenomenon might be that the poor have to spend money they generally do not have and therefore they have to think about optimal design. I do not like houses that were built by wealthy people. They could afford to explicitly think “How do I make it beautiful”, and this is why they fail to build something beautiful. Is is much like using too much make-up. Poor houses have no make-up on them, they transmit pure, naked beauty. Maybe this is the difference between folk and vulgar culture.

The same applies to people. Those walking the main streets of Yerevan have this, as they might describe it, “decent” look and feel that they aim for. This was one of the issues I had in Yerevan as a beginner photographer. I felt that when people want to look decent on purpose they inevitably lose a part of themselves, which they hide behind the way they dress and behave.

In other Armenian cities or in slum districts of Yerevan people care less about looking decent (they have other pressing matters to think about) and so they all look different, and every person’s uniqueness is more visible.

Yerevan wasn’t a city from my dream, but photography was one of the ways to accept the city as it is, and be able to perceive it’s beauty nevertheless, and give up being perfectionist. Perfectionism and relationships are not compatible, even if the relationship is with the city.

You catch a lot of people on your photographs by surprise. Have you ever run into trouble because of it?

No, not really. I have had trouble in Armenia, but never because of photographing.

Having said that I can understand why people are usually not happy when they see someone with a camera. They start wondering whether his intentions are good. I have learned to say that I am a photographer, then they have fewer questions or even sometimes show me something that they consider interesting to make a photo of.

I understand you also shoot in borderlands, what is pulling you there? What is it that you want to show there? Are frontier regions much different from what you can see in the center of the country?

Curiosity drew me there. Your perception is changing when you see buildings with the traces of fire, people, who are used to shootings, and a mountain with the military positions from where the fire comes from. You see a road which is unsafe, and other one which is safe, and you start thinking about many different things you did not think before.

I think most of Yerevanians do not know Armenia and do not get out of the city unless they have a good enough reason to do that – for example to see their grandmother in the country, this or that church, or to get drunk and burned at the shore of the Sevan lake.

I am not only interested in my city, I am interested in many places, and there are some pretty astonishing places in Armenia, and sometimes I discover them by accident.

Most of your photos are black and white. Why?

Why would they be in colour? Most of the time I consider colour to be an unnecessary and distracting piece of information. And when I feel I need that information, let’s say, when I feel it matters to show this yellow hat or that rusting door, I use colours.

Right now when thinking about your question I realized that maybe black and white is considered to be something like a “filter” or an “effect” today. I feel the opposite, I feel that colour is something I can add to the photo, if there is a reason to do that.

Another thought, which comes to my mind is that working with b/w is easier. As my photography class teacher once said – “the number of variables is smaller”.

Is there anything you would like to say about Yerevan or Armenia with words and not photos? Do you find it easier to tell Yerevan’s story with your camera? Is it better to record this country on camera than talk about it?

I am not sure. Maybe it is easier to look? Humans get a lot of information from pictures. It might take several pages of text to explain something that can be learned by taking a brief look at a photo.

Tell us a bit about tools and techniques you work with. Do you apply any post-processing / retouch to your photos?

I photograph with everything – on film, with the phone, or digital cameras. I have a collection of old lenses which I always carry in the backpack.

Retouch – almost never. Post-process? – yes, because otherwise the camera does it for me. It converts information from the sensor into a file according to predefined algorithms.

I configure my camera to save raw format files and I process them myself because the way the camera would process them is not what I want most of the time.

But I do not add or delete anything from the scene. I can correct exposure, or bring colours to the balance. And I am not very good at editing. I know some real Photoshop geeks, and I know people who can shoot photographs with technical excellence I lack.

However, I have a feeling that nothing important has changed since digital emerged – the photograph is still taken at the moment you fire the shutter.

Alright, I’ll bite. Why are dogs so important to you?

Alright, I’ll bite. Why are dogs so important to you?

There is something very touching about them. I am not sure that people who see my photos experience similar feelings as I do when I see those dogs.

I happen to be very sympathetic toward dogs. Actually this is true for any living creatures, but dogs are especially important to me. I have a history with dogs, I used to share a roof with them. I have no idea if I would love dogs if I have not had it. I think I would. I believe I would.

There is a feeling of sincerity in dogs, they are never fake. They do not realize they are being photographed and they do not try to look more decent.

When I drive I know there might be a dog, a cat or a snake crossing the road and I may not have enough time to break if I drive too fast. Thus I tend to drive slowly most of the time. A couple of months ago I damaged my car badly because I had to swerve in order to avoid hitting a dog. Well, I am happy the dog is okay.

–> Check more photo on Norayr Chilingarian’s Flickr.

Zuzanna Majer – Born in 86. Graduated from European Culture Study in Wrocław. Chief editor in PROwincja.